This is the USS Cassin Young, a destroyer memorial in Boston’s Charlestown Navy Yard, built in WW2.

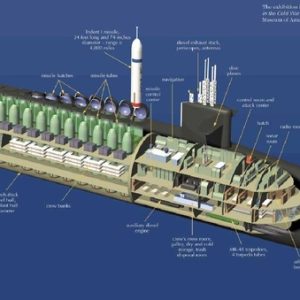

Every single plate of steel, including the gun shields, is no more than 3/8 inch steel. I watched them replate the bottom once and couldn’t believe how flimsy it was. You could shoot through it easily with a 9mm.

A .50 cal round is a big round. It would rip right through they ship and even possible pierce the bottom if it didn’t encounter an obstruction.

Actually yes. The standard ammunition belts included armor-piercing/incendiary rounds that would punch right through light steel plates used almost everywhere in a destroyer. But the main effect was to kill deck personnel who were lightly protected on the bridge and superstructure manning AA guns.

Even worse, destroyers and cruisers would routinely jettison their expensive oxygen-fueled torpedoes mounted on their upper deck when attacked by airpower. It was easy for .50 caliber rounds to set off a massive explosion if the Type-93 torpedoes were hit.

.50 BMG wouldn’t penetrate the hull for sure, and not even the deck in most cases. It might pierce some of the less armored spots on the superstructure.

They usually didn’t just shoot machine guns though; they’d drop bombs or fire rockets. Those could penetrate the deck.

But what the machine guns would do is kill crew in the open, and there typically was a significant number of them.

Particularly, most of the IJN’s short-med range anti-aircraft guns were not shielded at all. The Type 96 (pictured) was a very common one in dual or triple mounts, and most had zero protection for the crew. .50 fire would totally kill those guys if it hit.

I think the superstructures of Japanese destroyers were potentially vulnerable to .50 fire, given the light armor and the large windows on the bridge. While the thickness of deck armor varied by destroyer type and location, and AP .50 rounds could theoretically penetrate 0.75″ of armor, the specific ballistics (angle of impact, etc.) generally meant that such fire would inflict negligible structural damage even when it penetrated. The more significant effect of strafing warships was on topside AA gunners who had very little protection even on Japanese battleships, much less Japanese destroyers. Strafing also introduced the risk of detonating topside ordinance (e.g., depth charges and torpedoes), as well as starting fires, which were always a significant threat to any ship.

Strafing was decidedly more effective on even smaller craft or on non-warships (oilers, cargo ships, troop transports). Fighting in the Solomons in 1942 and 1943, the Japanese used many smaller ships (e.g., barges, junks, etc.) to transport troops and materiel between islands at night, hiding in lagoons by day. Strafing against these smaller targets tended to be very effective.

When strafing destroyers or non-combat ships in the South Pacific, one of the most effective platforms was not a fighter at all. It was the B-25 “strafer” model, engineered by formerly retired USN pilot and Philippine Airlines co-founder Pappy Gunn, who had begun such work on A-20 Havocs as a skunkworks project in conjunction with Australian and US Air Forces. Mounting 10–14 forward-firing .50 caliber machine guns, the B-25 strafers could typically carry 2,000 pounds or more of bombs. Many such B-25s combined low-level machine gun attacks with skip-bombing techniques (originally introduced to US pilots by the Australians) that yielded deadly results against destroyers and troop transports.

USN fighters had the ability to carry bombs by 1943, but one doesn’t often read about fighters combining skip-bombing techniques with strafing runs.

However, by late 1944, US F6F Hellcats and F4U Corsairs were modified to use 6 or 8 HVAR “Holy Moses” rockets in devastating low-level attacks. An HVAR AP rocket was about the size of a USN 5″ shell and could usually penetrate the side or deck armor of Japanese destroyers, inflicting devastating damage. While pilots required significantly more training to use rockets effectively, their effects on destroyers, non-warships, and deck crews of battleships was deadly.