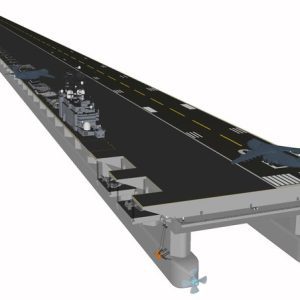

During my time on a carrier, we went through a hurricane not once, but twice. We were in the Atlantic returning to our home port but first, we had to dock at Norfolk so we could offload the Admiral and his staff. We hit the hurricane about 300 miles from the east coast. At first, it was just a lot of pitching up and down with green water coming over the bow.

We had two alert birds setup on the cats but it was determined that the aircraft would be okay since the storm was only a cat 1 at that time and the engine inlets and exhausts were covered.

We were inside about two hours when we got an emergency request for help for a merchant ship that had a medical case that needed immediate help.

We turned around and headed towards the direction of the ship. We were not quite out of the storm but we were able to launch our helicopter since we were in range. On the way there the ship reported that another Navy ship had gotten to them sooner and no longer needed assistance. Our ‘helo’ was called back and we again turned towards home but by this time the storm had grown into a cat 2 edging towards cat 3.

It was too late for us to try and divert around it so we had to continue into it. The ship was bow-up bow-down but now we were taking some heavy rolls, nothing like our sister smaller ships but for a carrier, they were pretty good rolls. When transiting across the ocean unless you are part of the Navigation and Engineering departments there isn’t anything you can do unless asked.

I went up to Pri-Fly (the ship’s “tower”) so I could see the whole length of the ship and watch the storm. I saw water coming over the bow at about 20 feet above the flight deck and I could see the expansion joints twisting (not a good thing). I also saw the engine covers being blown off the intakes of the planes on deck. It was strange to see seawater pouring out of the exhaust on them like a faucet. Mark two for the boneyard.

Seawater is very corrosive to metal. Seawater (which is laden with salt) going through an engine causes major issues and since you can never be sure that all of the water was rinsed out of the bearings, fittings, and cables it’s better to just junk it because the whole aircraft was basically being submerged in seawater: we could never get to all the spaces that the water did unless you tear the aircraft down completely.

Towards the aft of the ship I again saw the expansion joints in that direction twisting heavily. Our “Cherry Picker” (mobile crane) was lost overboard by snapping its tie-downs and falling over the side. I then heard the emergency secure signal being given because of our forward starboard hangar door had been knocked in by a side wave.

The door collapsed on top of two A7s on the hanger deck and crushed two sailors who got caught by the collapse. Water was now pouring into hanger deck and made walking in it impossible. Some compartments forward were flooded and the ship went to emergency stations with condition X-ray (securing all hatches and reporting to your assigned workspace).

The Damage Control Department was sent to shore up the hangar door and pump out the flooded areas. We sailed out of the storm about two or three hours later but pulling into Norfolk was out of the question since they had secured ahead of the storm and all ships that could sail were out to sea. No docking piers were ready to receive us.

We then turned south and went to our home port of Mayport, Florida. By the time we arrived the toll was six aircraft totaled (two on deck and four in the hanger deck), three sailors dead (two in the hanger and one who slipped and fell hitting his head), hanger deck door damaged beyond repair, all safety netting and edge antennas were torn off and the forward catwalks were peeled back on themselves. The expansion joints were severely damaged.

We lost the Cherry Picker and a forklift (no one saw this happen but it wasn’t there when we were able to make an assessment of the damage) over the side. The forward compartments were extremely flooded and now needed refurbishing and repair, They found several cracks in the island structure and we lost two major radar antennas.

We stayed at our home port and repairs were carried out at the dock. The ship made one more cruise after this and was decommissioned when it returned.

So to answer your question what’s it like? Terrifying, but you have a job to do and you do it. It’s part of life at sea. Do note though that sailing into a hurricane is not something that a ship would do unless there was no other choice. We knew that the storm was there and at the time it was determined not to be that severe.

A cat 1 storm doesn’t really affect a carrier that much because of its mass and weight. When we went into the storm at first it was no big deal. If we had not turned around and sailed back the direction we came perhaps we may have made it closer to Norfolk and not been in the storm when it grew in size and power but when a maritime emergency signal is given it is the duty of every close and available ship to render aid.

This signal is only given if lives are in peril. I will say this that to a man (at that time only men were on board ships) everyone did their best and their job. No one freaked out or started panicking.

That is what it is like inside a carrier in a heavy storm.